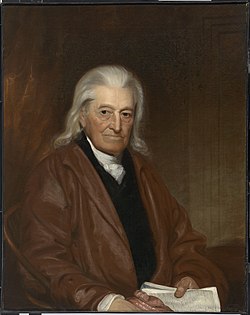

William Samuel Johnson was one of the best-educated signers of the United States Constitution, holding degrees from both Harvard and Yale. During the Revolutionary War, his loyalties were divided between his affection for his homeland and his respect for former British colleagues. This internal conflict led him to advocate for peace over violence. Throughout the war, Johnson acted repeatedly as a broker for peace, seeking to bring both sides to a resolution before ultimately emerging as one of the most influential delegates at the Constitutional Convention.

Early Life

William Samuel Johnson was born on October 7, 1727, in Stratford, Connecticut. He was the son of Samuel Johnson, the first president of King’s College (now Columbia University). Raised in an academic environment, Johnson graduated from Yale in 1744 and earned a Master of Arts in 1747. That same year, he was awarded an honorary master’s degree from Harvard. He studied law independently and passed the bar without formal training, establishing a legal practice in Stratford. His legal work, especially with New York City’s mercantile class, made him well-connected across British and colonial spheres on the eve of the Revolution.

Public Office

Johnson began his public service in the 1750s as a militia officer, later serving multiple terms in Connecticut’s colonial legislature—first in the lower house in 1761 and 1765, and then in the upper house from 1766, and again from 1771 to 1775. He participated in the Stamp Act Congress in 1765, where he supported colonial rights while still advocating reconciliation with the Crown.

From 1767 to 1771, Johnson served as Connecticut’s agent extraordinary to the British government, seeking to resolve disputes over land titles involving Native American tribes. In 1772, he was appointed a judge on the Connecticut Supreme Court. However, as tensions escalated, he declined an invitation to the First Continental Congress in 1774, instead advocating for moderation. In 1775, he traveled to Boston to negotiate with British General Thomas Gage in a final attempt to preserve peace. Though unsuccessful, his efforts were recognized when Oxford University awarded him a Doctor of Civil Law (D.C.L.) in 1776.

Constitutional Convention

In 1787, Johnson was appointed a delegate to the Constitutional Convention. He arrived on June 2 and did not miss a single session thereafter. A respected and moderate figure, Johnson championed the Connecticut Compromise, which resolved the dispute between large and small states regarding congressional representation. He also chaired the Committee of Style, which drafted the final version of the Constitution. Widely praised for his clarity, dignity, and calm judgment, Johnson signed the Constitution and played an active role in securing its ratification in Connecticut.

Role in the New Government

Following ratification, Johnson was elected one of Connecticut’s first U.S. Senators, serving from 1789 to 1791. During his term, he supported several important legislative initiatives, including the Judiciary Act of 1789, which established the federal court system.

Johnson’s enduring passion, however, was education. In 1787, he accepted the presidency of Columbia College (formerly King’s College), founded by his father. Balancing his duties in the Senate and at Columbia proved challenging, leading him to resign from Congress in 1791 to dedicate himself fully to the college.

Later Life

Johnson served as president of Columbia College until 1800. During his tenure, he helped rebuild and strengthen the institution after the disruptions of the Revolutionary War, laying the groundwork for its later prominence.

After retiring, Johnson returned to Stratford, Connecticut, where he lived quietly until his death on November 14, 1819, at the age of 92. He was buried in the Old Episcopal Cemetery in Stratford.

Legacy

William Samuel Johnson’s contributions to the founding of the United States and to the advancement of higher education endure to this day. A man of moderation, learning, and civic duty, he exemplified the values of the Enlightenment and played a vital role in shaping both American governance and academia.