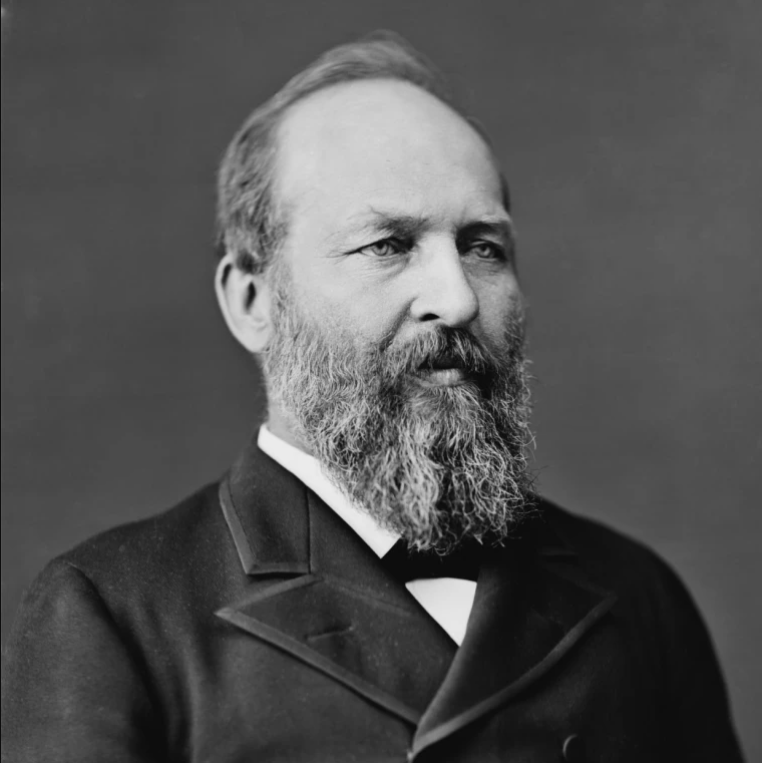

President James A. Garfield was the twentieth president of the United States. He served for four months until he was assassinated and succumbed to his wounds two months later.

Early Life

James Garfield was born into poverty in Ohio, in November of 1831. Garfield’s father died when James was a toddler, and James was raised by his strong-willed mother. He was often mocked by his peers for being both poor and fatherless, and turned to reading as an escape from reality. At age 16, Garfield left home and began working on a canal boat. In 1848, Garfield began attending Geauga Seminary in Ohio. In 1851, Garfield attended the Western Reserve Eclectic Institute in Ohio. He studied Greek and Latin, and taught these subjects at the Institute, though he was still a student.

In 1854, Garfield left the Institute and enrolled at Williams College, in Massachusetts. He graduated as the class salutatorian in 1856. He returned to Ohio and became a teacher at the Institute. However, the abolitionist movement made Garfield interested in politics. He began reading law under the supervision of a lawyer and was admitted to the bar in 1861.

The Civil War

Though Garfield had just received bar admission, when the Civil War began in 1861, he knew that he would join the Union Army in its fight against the South. As colonel, Garfield recruited many of his neighbors and former student to enlist in the 42nd Ohio Infantry Regiment. Garfield personally commanded the Battle of Middle Creek, which resulted in the Confederates withdrawing from the field. He was promoted to brigadier general as a reward for his success. Garfield later became chief of staff to Major General William Rosecrans. Rosecrans was dismissed after making a major error in strategy. Garfield was ordered to report to Washington and was promoted to major general.

Politics

Garfield’s name was placed on the ballot for the Congressional election of 1862. He won the seat for the House of Representatives. Garfield supported President Lincoln’s legislation and was part of the abolitionist movement. He also was a proponent of black suffrage. However, at times Garfield felt that Lincoln was not doing enough to push the South.

Garfield voted in support of the resolution that launched the first impeachment inquiry against President Andrew Johnson. Johnson was impeached by the House, but the Senate acquitted him.

Garfield was a member of the House Ways and Means Committee, and he favored the gold standard and opposed the issuance of paper money. Garfield advocated for the government to pay out silver and gold. He became the chair of the House Appropriations Committee. One major issue that the Appropriations Committee faced was the “Salary Grab of 1873,” which was the increase of compensation for Congressmembers by 50%. While Garfield opposed the increase, the public was outraged and many of Garfield’s constituents held him responsible. Garfield faced his narrowest congressional election, winning only 57% of the vote in 1874.

The Republican party lost control of the House for the first time since the Civil War in this election. Garfield lost his chair of the Appropriations Committee and was placed on the Ways and Means Committee as a member. He chose to run for the senate chair and was elected to Senate in 1880. His term was meant to start in March of 1881, but Garfield never took office. Instead, Garfield was nominated for president in 1880 and won.

Some of Garfield’s objectives during his presidency was to reform the civil service system, particularly in the Post Office. Garfield demanded the resignation of the Assistant Postmaster General and ordered prosecutions of post office members who escalated mail route costs and divided profits amongst themselves. Garfield also proposed a universal education system funded by the federal government, believing that this would be the best way to improve the state of African American civil rights. He also appointed several African Americans to prominent positions in government, such as Frederick Douglass, John Langston, and Robert Elliot.

Garfield was assassinated by Charles Guiteau, who was determined to gain federal office. Guiteau was thought to have many mental illnesses, and no one thought he was deemed fit for any government position. Guiteau thought he had been passed over due to his political affiliations and believed the only way to end the Republican party’s reign was to kill Garfield. In the early morning of July 2, 1881, Garfield was waiting for a train in Washington when Guiteau shot Garfield twice, once in the back and once in the arm. Garfield died three months later, in September of 1881. Some historians and medical experts argue that if Garfield had been alive today, he would have survived the shooting. It was common in those days for doctors to insert their unsterilized fingers into the wound to search for the bullet, which increases the likelihood of infection. Garfield was laid to rest in Cleveland. His death at the hands of a mentally ill office seeker made the public aware of the need for civil service reform legislation. The Pendleton Act took effect, a reform effort that reversed the spoils system and instead granted appointments based on merit or competitive examination.