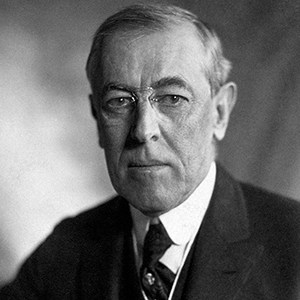

Thomas Woodrow Wilson served as the 28th President of the United States from 1913 to 1921. Wilson was a leading force in the Progressive Movement, using his presidency to pass a series of reforms, including the Federal Reserve Act and the Clayton Antitrust Act.

Early Life

Wilson was born on December 28, 1856 in Staunton, Virginia. He graduated from Princeton University undergrad and received a Ph.D. in political science from Johns Hopkins University. After earning these degrees, Wilson embarked on an academic career. He taught at Cornell University, Bryn Mawr College, and Wesleyan University before being elected as President of Princeton in 1902. In 1910, he was elected the Governor of New Jersey, serving until he was elected President of the United States in 1912.

Presidency

In the presidential election of 1912, Wilson campaigned on a platform of “New Freedom,” which emphasized individualism and states’ rights. Once in office, Wilson signed a flurry of reform bills. The Underwood Act lowered tariffs, while the Revenue Act established the country’s first federal income tax. The Federal Reserve Act created a decentralized central bank and provided the country with a much-needed elastic money supply. To crack down on unfair and anti-competitive business practices, he bolstered the nation’s antitrust laws and established a Federal Trade Commission. Under Wilson, Congress also passed a number of labor laws intended to protect workers, including laws regulating child labor and restricting railroad workers to an eight-hour day

World War I

Wilson’s second term was dominated by World War I. On April 2, 1917, he reluctantly asked Congress to declare war on Germany in order to make “the world safe for democracy.” To support the war effort, Wilson signed the Selective Service Act, which reestablished a national draft.

The United States’ involvement in World War I sparked protests. In response, Wilson proposed the Espionage Act of 1917 and the Sedition Act of 1918, which were intended to suppress criticism of the war effort. At the same time, Wilson supported the women’s suffrage movement and endorsed the ratification of the Nineteenth Amendment, which gave women the right to vote.

In January 1918, Wilson went before Congress to outline the country’s goals for peace. Known as the Fourteen Points, one of Wilson’s aims was to create “a general association of nations…affording mutual guarantees of political independence and territorial integrity to great and small states alike.” The proposal formed the foundation for the League of Nations.

After the Germans surrendered in November 1918, Wilson traveled to Europe to help secure a lasting peace. One year later, he was awarded the Nobel Peace Prize for his efforts. Nonetheless, the Treaty of Versailles, which included the Covenant of the League of Nations, was not universally accepted, particularly at home, where Republicans were staunchly opposed.

In 1919, Wilson collapsed under the strain of a U.S. public speaking tour to rally support for ratification of the treaty, suffered a series of strokes, and never fully recovered. While those close to Wilson shielded the extent of his incapacity from the public, questions about his fitness to lead the country later prompted the adoption of the 25th Amendment.

Death

Wilson died at his home on February 3, 1924 of a stroke and additional heart-related problems.