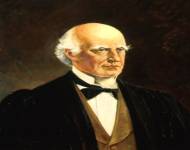

John Archibald Campbell (1853-1861)

John A. Campbell lived from 1811 to 1889.

Early Life

Campbell was born near Washington, Georgia. Deemed a “child prodigy,” he proved his intellectual capabilities early on in life. Campbell achieved impressive academic accomplishments, including graduating from Franklin College (now the University of Georgia) with high honors at the age of 14. After graduating from Franklin, he immediately enrolled in the United States Military Academy in West Point, New York. Campbell, however, faced several challenges during his tenure there. Aside from ranking at the bottom third of his class at the end of his first three years, Campbell was also forced to deal with the sudden passing of his father, Colonel Duncan Greene Campbell. His father’s estate had accumulated a large amount of debt, forcing his family to sell their home. As a result, Campbell was left with no option but to resign from the academy.

Legal Career

Following his resignation, Campbell returned home to Georgia, where he decided to pursue a legal career. He began reading law under the guidance of his uncle, John Clark, the former governor of Georgia. In 1829, at the age of 18, Campbell was admitted to the Georgia bar. After moving to Alabama and earning a reputation as a talented lawyer, Campbell was elected state representative. He served two terms in the state legislature, where he firmly established himself as a Jacksonian Democrat. During this time, Campbell continued to rise as one of the most sought-after attorneys in the state of Alabama. Arguing six cases in front of the Supreme Court before 1852, one of Campbell’s most notable stances was his stance on slavery. Although Campbell was pro-slavery, he managed to express his opinions on the topic in a manner that appeased the northern abolitionists and allowed for well thought out compromises to be made between the two sides.

Appointment to the Supreme Court

When President Franklin Pierce’s candidate for the Supreme Court was rejected in 1853, the members of the Supreme Court unanimously requested that Campbell be chosen to fill the open seat; a politically unorthodox method that was ultimately successful due to Campbell’s ability to strike a middle ground on issues related to slavery–something Pierce’s candidate could not do. His principal struggle while on the bench was attempting to stop the secessionist fever from spreading. Campbell refused to entertain the idea of a secession, and even freed his own slaves prior to taking a seat on the Supreme Court to support his position. When confronted with controversial cases packed with political consequences, Campbell often supported rulings that would cause the least tension between the North and South. After the Confederacy formed in 1860, he attempted to act as a mediator between the Northerners that refused to recognize the Confederacy as a state and the Confederacy itself, but his efforts to strike a middle ground fell short. Disappointed by his failed efforts, Campbell resigned from the Supreme Court and moved back to his home in Mobile, Alabama.

Later Years

Following his attempts to mediate with the North, Southerners viewed Campbell as a traitor. After receiving several death threats, Campbell left the south and moved to New Orleans, where he eventually set up his own practice. Shortly after, the Confederacy sought out Campbell to serve as their Assistant Secretary of War. He accepted the position, but was clear on his stance for peace. In 1865, Campbell met with President Abraham Lincoln to negotiate the conditions of the Confederacy’s surrender. After the two came to an agreement, the President was assassinated. Campbell was then imprisoned, accused by the North of having misrepresented the President’s views toward surrender during the meeting. These charges, however, were dropped four months later. After his release, Campbell returned to New Orleans, where he resumed his law practice. Campbell once again argued several cases before the Supreme Court, including the Slaughterhouse cases, and a number of other cases designed to impede radical reconstruction in the South.

Death

Campbell slowly began to decrease his caseload, but never fully retired from the practice of law until dying of natural causes in 1889.

Notable Cases

Slaughterhouse cases (1850-1900)

Dred Scott v. Sandford (1857)