SCOTUS Unanimously Upholds Faithless Elector Laws

In Chiafalo v. Washington, 591 U. S. ____ (2020), the U.S. Supreme Court upheld state “faithless elector” laws. The justices unanimously ruled that states may enforce an elector’s pledge to support his party’s nominee—and the state voters’ choice—for President.

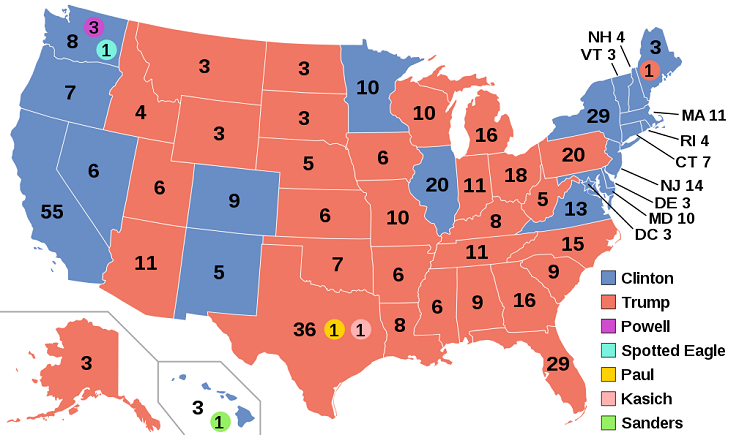

Electoral College

The Electoral College was the result of a compromise by our Founding Fathers between giving Congress the power to elect the President and resting the power solely with the American people. Under our current election system, the candidate who wins 270 or more Electoral College votes is elected President, not the candidate who receives the majority of the votes cast by the voting public. However, electoral votes are allocated based on the results of the popular vote in each state. Each state has a designated number of electors, which is determined by the numbers of members its sends to Congress.

Facts of the Case

The States have devised mechanisms to ensure that the electors they appoint vote for the presidential candidate their citizens have preferred. With two partial exceptions, every State appoints a slate of electors selected by the political party whose candidate has won the State’s popular vote. Most States also compel electors to pledge to support the nominee of that party, and 15 States impose some kind of sanction for noncompliance. Almost all of these States immediately remove a so-called “faithless elector” from his position, substituting an alternate whose vote the State reports instead. A few States impose a monetary fine on any elector who flouts his pledge.

Three Washington electors, Peter Chiafalo, Levi Guerra, and Esther John (the Electors), violated their pledges to support Hillary Clinton in the 2016 presidential election. In response, the State fined the Electors $1,000 apiece for breaking their pledges to support the same candidate its voters had. The Electors challenged their fines in state court, arguing that the Constitution gives members of the Electoral College the right to vote however they please.

The Washington Superior Court rejected that claim, and the State Supreme Court affirmed, relying on Ray v. Blair, 343 U. S. 214, 228 (1952). In Ray, the Supreme Court upheld a pledge requirement —though one without a penalty to back it up. The Court rejected the argument that the Constitution “demands absolute freedom for the elector to vote his own choice.” The Court, however, reserved the question whether a State can enforce that requirement through legal sanctions.

Supreme Court’s Decision

By a vote of 9-0, the Supreme Court affirmed. “The Constitution’s text and the Nation’s history both support allowing a State to enforce an elector’s pledge to support his party’s nominee—and the state voters’ choice—for President,” Justice Elena Kagan wrote on behalf of the Court.

In her opinion, Justice Kagan acknowledged that the Constitution is “barebones about electors.” It provides only that states will appoint electors, who meet and cast ballots for the president, and send the results to the Capitol. “Those sparse instructions,” Justice Kagan explained, “took no position on how independent from—or how faithful to—party and popular preferences the electors’ votes should be.”

Justice Kagan highlighted that Article II, §1 gives the States the authority to appoint electors “in such Manner as the Legislature thereof may direct,” which the Court has previously interpreted as “conveying the broadest power of determination” over who becomes an elector. The Court further reasoned that the power to appoint an elector (in any manner) includes power to condition his appointment, absent some other constitutional constraint. As Justice Kagan emphasized, nothing in the Constitution “expressly prohibits States from taking away presidential electors’ voting discretion as Washington does.”

Justice Kagan went on to explain that the Electors’ constitutional claim has “neither text nor history on its side.” With regard to history, Justice Kagan noted that Washington’s law reflects a tradition more than two centuries old. “In that practice, electors are not free agents; they are to vote for the candidate whom the State’s voters have chosen,” she wrote. In concluding her opinion, Kagan summarized the Court’s reasoning as follows:

Article II and the Twelfth Amendment give States broad power over electors, and give electors themselves no rights. Early in our history, States decided to tie electors to the presidential choices of others, whether legislatures or citizens. Except that legislatures no longer play a role, that practice has continued for more than 200 years. Among the devices States have long used to achieve their object are pledge laws, designed to impress on electors their role as agents of others. A State follows in the same tradition if, like Washington, it chooses to sanction an elector for breaching his promise. Then too, the State instructs its electors that they have no ground for reversing the vote of millions of its citizens. That direction accords with the Constitution—as well as with the trust of a Nation that here, We the People rule.

Previous Articles

SCOTUS Decision in Bowe v. United States Is First of the 2026 Term

by DONALD SCARINCI on February 5, 2026

In Bowe v. United States, 607 U.S. ___ (2026), the U.S. Supreme Court held that Title 28 U.S.C. § ...

SCOTUS Rules State Can’t Immunize Parties from Federal Civil Liability

by DONALD SCARINCI on January 29, 2026

In John Doe v. Dynamic Physical Therapy, LLC, 607 U.S. ____ (2025) the U.S. Supreme Court held that...

Supreme Court to Address Racial Discrimination in Jury Selection

by DONALD SCARINCI onWhile the U.S. Supreme Court has concluded oral arguments for the year, it continues to add cases t...

The Amendments

-

Amendment1

- Establishment ClauseFree Exercise Clause

- Freedom of Speech

- Freedoms of Press

- Freedom of Assembly, and Petitition

-

Amendment2

- The Right to Bear Arms

-

Amendment4

- Unreasonable Searches and Seizures

-

Amendment5

- Due Process

- Eminent Domain

- Rights of Criminal Defendants

Preamble to the Bill of Rights

Congress of the United States begun and held at the City of New-York, on Wednesday the fourth of March, one thousand seven hundred and eighty nine.

THE Conventions of a number of the States, having at the time of their adopting the Constitution, expressed a desire, in order to prevent misconstruction or abuse of its powers, that further declaratory and restrictive clauses should be added: And as extending the ground of public confidence in the Government, will best ensure the beneficent ends of its institution.